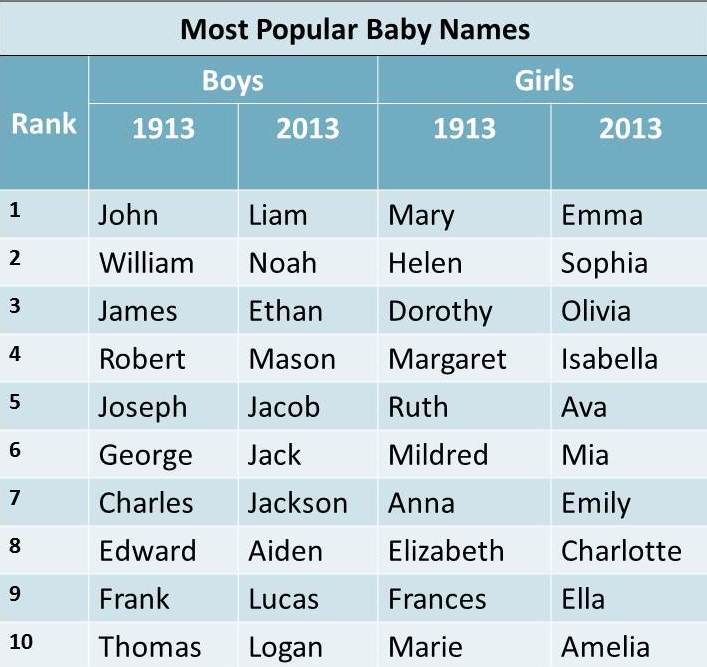

Many new parents think long and hard about what name they will give their newborn. There are countless books and websites devoted to helping you pick the name that sounds the best and means the most to you. The importance of bestowing a name is not a new phenomenon; it has a very long and important history. Some of the most popular names given in the United States today can be traced to ancient words, even if the history is only visible through a popular trend, as in the rise of –en names in English. 5 of the 10 most popular names of 2013 end in [ən], compared to the complete absence of these names in 1913. Some of these names are of Hebrew descent, and are unrelated to the others. Two in particular, Logan and Aiden, are of Celtic descent. The [ən] in both of these names is a diminutive marker (“little hollow“ and “little fire” respectively). Patterns such as this one can be found in many modern personal names, and typically have their roots in an ancient language.

Naming children in modern society is taken very seriously, but a personal name does not have the same weight as it did long before our current names existed. Indo-European culture placed a large emphasis on fame and the deeds that brought fame. Naming a child was not just about selecting a series of arbitrary sounds that could be associated with each individual, it was about cementing the future reputation of the child. The naming process of the Indo-European culture was almost ritualistic in nature. There is evidence for very similar rituals in multiple cultures. After the child was born, the parents would wait approximately 9 days during in which time the mother could recover from childbirth. After the 9 day resting period, the mother was bathed and the child was given a name. This process, or a similar one, is repeated in Indian, Greek, Roman, and Germanic cultures, leading us to believe that the practice was a descendent from the parent of them all, Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

Why was naming so important that the process became sacred? The ultimate goal of an IE individual, particularly an individual from the more priveleged classes, was to become a legend. The poet was one of the most important roles in the society; It was his job to make sure that heroes and their deeds were well known throughout the civilization. More than that, it was important that stories of their successes continued to be told long after they were gone. In fact, the words for “fame” and “name” are related, sometimes even synonymous, in several daughter languages of IE. Vital to the success of these epics was a powerful name. An epic tale about a man named “Weak in battle” might not bode well for the poet, or for “Weak in battle” himself.

Indo-European names reflect the values of their culture, namely involving fame, the guest/host relationship, gods, battles/strength, and leadership. Many of our own names are descendant from Indo-European names. Some commonly known names as examples:

- Albert: Old High German Adalbert

- Adal: noble (< Proto-Germanic *athal-; cf. German Edel-weiss)

- Beraht: bright (From PIE *bhreh1ǵ-; cf. Sanskrit bhrā́jate ‘shines’)

- Ludwig: Germanic Hludwig

- Hlud: fame (< PIE *ḱlutó- ‘that which is heard’; cf. English loud)

- Wig: warrior (< Proto-Germanic *wig-; cf. Old English wiga ‘warrior’)

- Fergus: Gaelic Fearghus

- Gaelic fear: man (< PIE *u̯ih1ró- ‘man, hero; cf. English were-wolf ‘man-wolf’, vir-ile ‘manly’)

- Gaelic gus: vigour (< PIE *geu̯s- “to taste”; cf. English choose)

Indo-European names typically consisted of 2 words compounded to make a name, called a dithematic compound (fame + warrior). The name of the father would sometimes be broken apart to create a name for the son, similarly to the naming practices of race horses in modern culture. A father named Dinoklē̃s (fear + strength) in Greek might name his son Dinokrátēs (fear + fame). You can imagine that after splitting the names of the men of a society for so long, the names might begin to sound like nonsense. While many personal names from the English language among other Indo-European languages can be traced directly back to PIE, there are also cases in which the words themselves were passed on to daughter languages, and then the names were developed.

The units that make up these names tell us a great deal about PIE culture. What was important to the people? What did they want to achieve? Like many daughter cultures, the proto-culture was hierarchical, with royalty, religious figures, and warriors in the upper classes. Many great epics are known about the feats of kings and warriors. The hero of the story typically interacts with the gods in some way. The hero is a brave man who must defeat a force of evil using strength and cunning. Names such as Greek Diogénēs, “born of Zeus,” Old High German Hlúdwīg (later Ludwig), “loud in battle,” and Old Persian Xšayāršā (Xerxes), “ruling over men”, display these cultural characteristics manifested in a name. Another valued component of the proto-culture was the guest-host relationship. This practice has been lost to some degree in North American culture, but was of vital importance in PIE culture. You may recall that according to Homer in the Iliad, the Trojan War was the product of a violation of xenia, the Greek word for this concept of the guest-host relationship. Greek literature is full of references to hospitality, indicating to us its importance and severity. Names from several IE branches include references to guests (Runic Germanic Hlewa-gastiz, “Fame-guest”). Strength, another staple in the name repertoire, is still highly valued in the modern world. Warriors were respected as upper members of IE society, and names with elements such as ‘battle’ (Hil-da), ‘glory’ (Hera-kles), or even ‘spear’ (Ger-ald) were common.

In examining the popular personal names from Indo-European culture, we see where the ideals of the people lay. The goal of an IE individual was to be strong and successful in battle, to be a good leader or host, and to make sure that generations to come would know about it. Many of our names can be traced back to these roots, and many aspects of our culture can be traced back to the proto-culture. If you would like to study the history of your own name or learn more about Proto-Indo-European culture and daughter branches, see the “For further reading” section below.

For Further Reading: